Chemical space(s)

An interesting perspective on “Chemical Space” was penned by Jean-Louis Reymond recently, titled “Chemical space as a unifying theme for chemistry”. Reymond argues for a total, unifying “Chemical Space” concept as opposed to “a” Chemical Space. With the indefinite article in front of it, it becomes downgraded to just refer to specific categories of molecular sets, like for example natural products, or some specific vendor’s make-on-demand library. Of course, Reymond is well placed to make this argument as the trailblazer who exhaustively enumerated all possible chemical structures under specific constraints.

Reading this made me think of a book I recently read: “Philosophical Chemistry: Genealogy of a Scientific Field” by Manuel DeLanda. On the whole, this book was quite puzzling to me: the case studies read to me as a rather straight history of chemistry (1750-1900), to the extent I was wondering who the intended reader of this book is. To someone with a chemistry background, it is probably a little bit too simple, although of historical interest. To a layperson reader, who is not able to judge which theories and practices will turn out to become consensual, the reading must be a confusing endless listing of silly sounding historical theories (I knew the ending already but I was still cheering for phlogiston).

But the justification for that whole historical elaboration is DeLanda’s critique of scientistic thinking. And that’s where the connection with Reymond is to be found: for DeLanda, Science is a population of individual scientific fields, which differentiate, specialize, on the whole diverge.

In DeLanda’s words:

There is not even a discernible convergence towards a grand synthesis to give us hope that even if the population of fields is highly heterogeneous today, it will one day converge into a unified field. On the contrary, the historical record shows a population progressively differentiating into many subfields, by specialization or hybridization, yielding an overall divergent movement.

and later:

The population of scientific fields is divergent, that is, it is not converging on a final theory; and that the domain of most fields becomes more complex with time, presenting practitioners with a moving target and precluding any dream of a final truth.

I believe that concern applies to the universalizing mission of chemical space as well: because of endlessly diverging chemical specializations, mapping all species of this domain (i.e. chemical compounds and reactions) onto a vast, unified space becomes an impossible task: what is nearby from one perspective is distant from another (for example: from the point of view of pharmacology diphenylprolinol and desoxypipradrol are quite close. From the point of view of organocatalysis they are not.). What counts as distinct species is field and task dependent: tautomers, conformers, enantiomers may differ for some properties of interest or they may not. What deserves to even be included at all is up for discussion: unstable transient species may be mechanistically meaningful or stable at ultra-low temperatures. Do Olah’s and Brown’s norbornyl cations occur in the same chemical space?

Perhaps just like our physical universe, chemical space is heterogenous, filled with uncountable curiosities, yet mostly filled with empty dead stuff and physically unbridgable distances between its contents. And traversal and observation of it tends to be local.

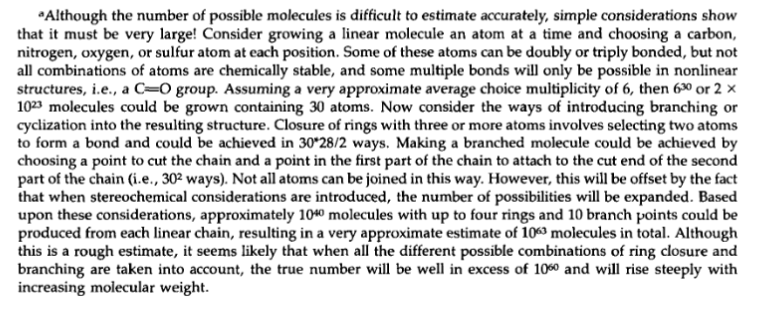

By the way, some years ago I needed to chase down the famous “1060” number which is often quoted as one estimate of the size of chemical space. To my surprise, the argument was made in a footnote and is of the “Napkin Math” variety. See the screenshot (reproduced without permission from Bohacek et al) below.

For higher and lower estimates of the size of chemical space, check out this article by Polishchuk and coworkers. The new estimate these authors provide is also based on extrapolation from Reymond’s GDB work.